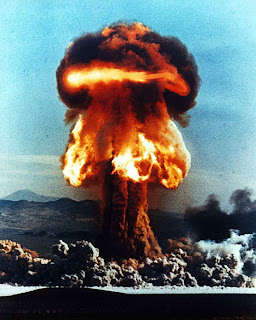

The Iranian aspiration to nuclear weaponry is causing this complex problem to assume the dimensions of a time bomb. Internal struggles within the Bush administration have blocked the momentum toward a military operation. In Israel, there has been more serious consideration of such an option, but it has not matured into a decision. However, the political reality has changed more than the military-technological situation. The agonies of grappling with the decision have been transferred to the new holders of the same offices - more than anyone else, to president-elect Barack Obama, to the person who will head the government of Israel and, in addition, to their cabinet ministers, top intelligence and air force professionals and various military advisors.

A week ago, Obama expressed public lack of confidence in American intelligence when he refused to be impressed by the quality of the briefing he received from the Central Intelligence Agency. Even if he replaces the experts and the chiefs, Obama will have to deal with two eternal verities: Iran is continuing to progress along its road to nuclear-weapons capability, and Israel will not agree to this. Some people will tell Obama they doubt whether it is a foregone conclusion, but Obama will be compelled to assume that the scenario liable to be realized is at the grave end of the spectrum. Iran is conducting a series of miniature, and for the most part unilateral, wars in the region. That its victims have refrained from inflicting damage in return has increased the appetite of Suleimani and his colleagues, who behave as though they are immune from what happened to Mughniyeh.

Prior to Obama's inauguration, at least three regular U.S. situation assessments are slated to relate to the Iranian issue: a National Intelligence Estimate, a review of the military situation (the "threat" versus the "response") by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and a reexamination of the Middle East strategy, which Petraeus announced at the Senate hearing prior to his appointment as commander of CENTCOM, the central command of the U.S. Army. It is in the space between these documents and Obama's campaign platform that a new American policy will find its place: more flexibility in the envelope of contacts with Iran, without a relaxation of the aggregate of pressures to stop its military nuclearization, its indirect war on Israel and the United States, and its bullying activity to achieve supremacy in and around the Persian Gulf.

Obama will also quickly come up against the interlocking realities of foreign policy. His election promise of a quick evacuation from Iraq will melt away in a graduated timetable, in part because the promise has already been perceived as hasty in Saudi Arabia and Turkey. In Iran he prefers dialogue, followed by defense, with attack only treated as a last resort. Defense against Iran, however, complicates matters vis-a-vis the Russians, who are more and more vociferously opposed to the deployment of American interception missiles and radar systems in Poland and the Czech Republic.

The two most important spokesmen for the U.S. Army on the question of Iran are Petraeus and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Michael Mullen. In a lecture after Obama's victory, Mullen said that the Middle East is his top concern, that three-quarters of the available American military force is invested there, and that Iran is undermining the region's stability, both as a catalyst for a nuclear arms race and as the benefactor of terror organizations. Petraeus, in his responses to the Senate committee, said similar things.

The first Gulf War in Iraq in 1991, in Obama's opinion, was the model of a successful war: diplomatic alliances, few losses, low costs (he ignores 12 dry years of attrition in air strikes that followed the cease-fire). In that war, the American alliance was joined not only by Saudi Arabia and Egypt, but also by Syria. Today, the assessment of the Israel Defense Forces is that Syria, for the very same reason of competition with Iraq, which borders it, will maintain its alliance with Iran. In order to convince himself - and the public and Congress - that a confrontation with Iran is inevitable, Obama will first try to carry out a dialogue with the Iranian leadership. The U.S. Army supports this. Petraeus has suggested reaching out, "to help moderate, pragmatic elements that might influence the internal Iranian debate over Iran's foreign policy and long-term security interests."

If the previous president, Mohammad Khatami, who fits Petraeus' qualifications, participates in the election next spring, and defeats his provocateur successor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Obama will lift the precondition for dialogue that was established by the Bush administration: the cessation of uranium enrichment. Iran will present to the world a more relaxed and demure face, one that is no longer calling for the destruction of Israel, and at the same time it will consistently move closer to a bomb, because in Tehran it isn't the president who decides what happens, but rather Khamenei and the Islamic clerics, and alongside them Suleimani and the Revolutionary Guard.

The next government in Tehran will be established in June. By the end of the year Iran will have in its hands sufficient weapons-quality nuclear material for a bomb. Thus the autumn of 2009 will be the time for decision, in Washington and in Jerusalem. If there are those (in Iran, Europe, America or Israel) who are toying with the illusion that the election of Obama will change the face of the Bush policy and prevent the use of military force to thwart the Iranians' nuclearization, they are destined to find themselves disabused of that notion.

A week ago, Obama expressed public lack of confidence in American intelligence when he refused to be impressed by the quality of the briefing he received from the Central Intelligence Agency. Even if he replaces the experts and the chiefs, Obama will have to deal with two eternal verities: Iran is continuing to progress along its road to nuclear-weapons capability, and Israel will not agree to this. Some people will tell Obama they doubt whether it is a foregone conclusion, but Obama will be compelled to assume that the scenario liable to be realized is at the grave end of the spectrum. Iran is conducting a series of miniature, and for the most part unilateral, wars in the region. That its victims have refrained from inflicting damage in return has increased the appetite of Suleimani and his colleagues, who behave as though they are immune from what happened to Mughniyeh.

Prior to Obama's inauguration, at least three regular U.S. situation assessments are slated to relate to the Iranian issue: a National Intelligence Estimate, a review of the military situation (the "threat" versus the "response") by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and a reexamination of the Middle East strategy, which Petraeus announced at the Senate hearing prior to his appointment as commander of CENTCOM, the central command of the U.S. Army. It is in the space between these documents and Obama's campaign platform that a new American policy will find its place: more flexibility in the envelope of contacts with Iran, without a relaxation of the aggregate of pressures to stop its military nuclearization, its indirect war on Israel and the United States, and its bullying activity to achieve supremacy in and around the Persian Gulf.

Obama will also quickly come up against the interlocking realities of foreign policy. His election promise of a quick evacuation from Iraq will melt away in a graduated timetable, in part because the promise has already been perceived as hasty in Saudi Arabia and Turkey. In Iran he prefers dialogue, followed by defense, with attack only treated as a last resort. Defense against Iran, however, complicates matters vis-a-vis the Russians, who are more and more vociferously opposed to the deployment of American interception missiles and radar systems in Poland and the Czech Republic.

The two most important spokesmen for the U.S. Army on the question of Iran are Petraeus and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Michael Mullen. In a lecture after Obama's victory, Mullen said that the Middle East is his top concern, that three-quarters of the available American military force is invested there, and that Iran is undermining the region's stability, both as a catalyst for a nuclear arms race and as the benefactor of terror organizations. Petraeus, in his responses to the Senate committee, said similar things.

The first Gulf War in Iraq in 1991, in Obama's opinion, was the model of a successful war: diplomatic alliances, few losses, low costs (he ignores 12 dry years of attrition in air strikes that followed the cease-fire). In that war, the American alliance was joined not only by Saudi Arabia and Egypt, but also by Syria. Today, the assessment of the Israel Defense Forces is that Syria, for the very same reason of competition with Iraq, which borders it, will maintain its alliance with Iran. In order to convince himself - and the public and Congress - that a confrontation with Iran is inevitable, Obama will first try to carry out a dialogue with the Iranian leadership. The U.S. Army supports this. Petraeus has suggested reaching out, "to help moderate, pragmatic elements that might influence the internal Iranian debate over Iran's foreign policy and long-term security interests."

If the previous president, Mohammad Khatami, who fits Petraeus' qualifications, participates in the election next spring, and defeats his provocateur successor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Obama will lift the precondition for dialogue that was established by the Bush administration: the cessation of uranium enrichment. Iran will present to the world a more relaxed and demure face, one that is no longer calling for the destruction of Israel, and at the same time it will consistently move closer to a bomb, because in Tehran it isn't the president who decides what happens, but rather Khamenei and the Islamic clerics, and alongside them Suleimani and the Revolutionary Guard.

The next government in Tehran will be established in June. By the end of the year Iran will have in its hands sufficient weapons-quality nuclear material for a bomb. Thus the autumn of 2009 will be the time for decision, in Washington and in Jerusalem. If there are those (in Iran, Europe, America or Israel) who are toying with the illusion that the election of Obama will change the face of the Bush policy and prevent the use of military force to thwart the Iranians' nuclearization, they are destined to find themselves disabused of that notion.

Iran

Obama

No comments:

Post a Comment